From 20 to 2,000 engineers on GitHub: Azure, GitHub and our Open Source Portal

November 18, 2015

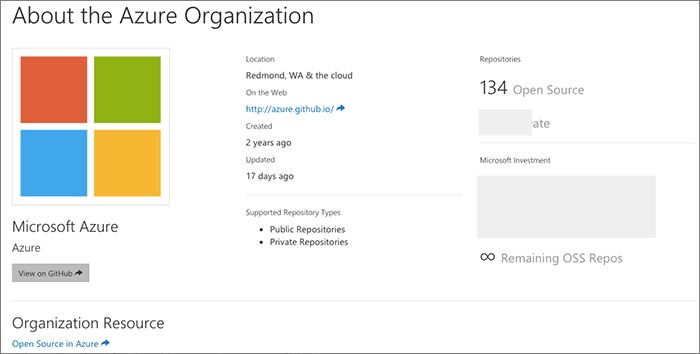

On the Microsoft Azure team our GitHub presence today is operating at more than an order of magnitude from where we were when we started in 2011. We have grown from 20 members of our GitHub organization to over 2,000 engineers participating from across many parts of Microsoft. We also manage several organizations, including one dedicated for samples. To help manage this growth we've tried a number of experiments, built some tools, and today I wanted to walk you through our Open Source Portal for GitHub, a Node.js app that has helped us move to a self-service model for onboarding employees and helping with many outbound GitHub tasks. We open sourced the web app last week.

View open source on GitHub: Azure/azure-oss-portalThis portal is not rocket science (and neither is this post). There's enough innovation happening in the industry and within Microsoft to keep everyone quite busy on the rocket science part, but we still owe it to our engineers to help reduce friction and let them do their best work. Instead this exercise was about taking the best of open source and hacking something together along with GitHub's API to automate the things that we can.

I first hacked together an early version of this portal over the holidays almost a year ago and am very happy to be able to point people to the azure-oss-portao open source repo up on GitHub. Across Microsoft we're investing in improving how our engineers embrace open source and I hope that this can be a a piece of that puzzle.

In this post I will introduce our portal, the tech stack and Azure services behind it, walk through the end user features, talk about some of the choices we have made regarding managing our GitHub organizations, and then jump into how to configure the portal for your own use. I'll close with a few comments about what might be next.

FYI: this post is my personal take on the portal work. Opinions are mine. Oh, and this post is going to be very long. It might be time to grab a venti coffee, cozy up, and use some bandwidth to download some screenshots.

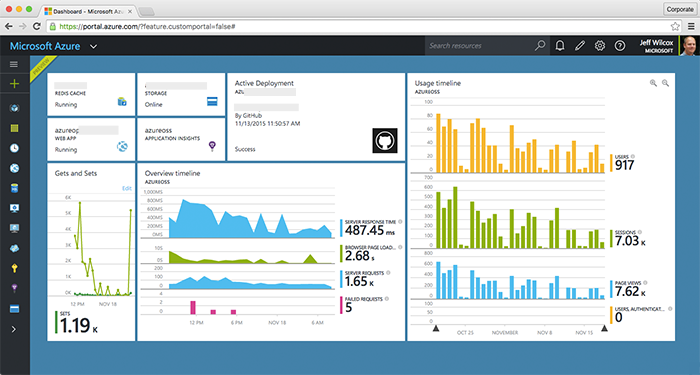

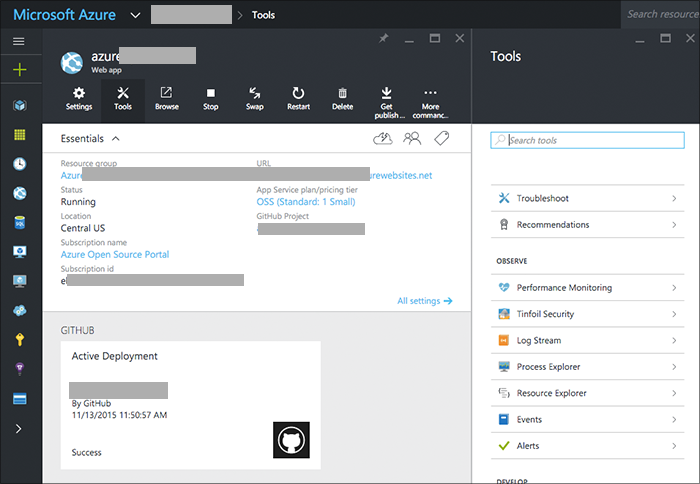

A few Azure services help to run the experience. Here you can see my view of the Azure Portal with interesting stats and use info, including Redis cache hits and misses.

Hope this helps! Please let me know what you think on Twitter (@jeffwilcox).

A brief history of our GitHub presence

Today Microsoft as a whole is embracing GitHub faster than ever and I'm personally very, very excited to be a part of this embrace that is happening. It's great to be able to share some of my perspective and opinion with you now.

In 2011 we set out to open source a set of Azure libraries across many languages, ship a new cross-platform command line and PowerShell experience, and were working on preparing to ship Mobile Services. Once the projects were greenlit the team huddled with a group of lawyers, pulled out "Uncle Steve's Amex", appointed a set of GitHub administrators and got to work.

I imagine this is how nearly every large GitHub organization has started, too. It grows fast from there. GitHub is a rocking service, but it isn't necessarily designed for scaling to thousands of organization members today: it supports that number of users, it's just that many of the key tasks, such as inviting people to the organization, involve what is often a manual workflow. GitHub provides an API that can help, but getting from that to a useful experience turns out to be the trick today.

What are some of the questions that we would like to answer about our GitHub presence and our organization members? Here's a sample:

- Who is this random GitHub user? Are they an employee?

- Is this person in our contributor license agreement (CLA) database?

- Does this person still work at the company?

- Should this person be a member of a team on GitHub?

Introducing the Azure Open Source Portal for GitHub

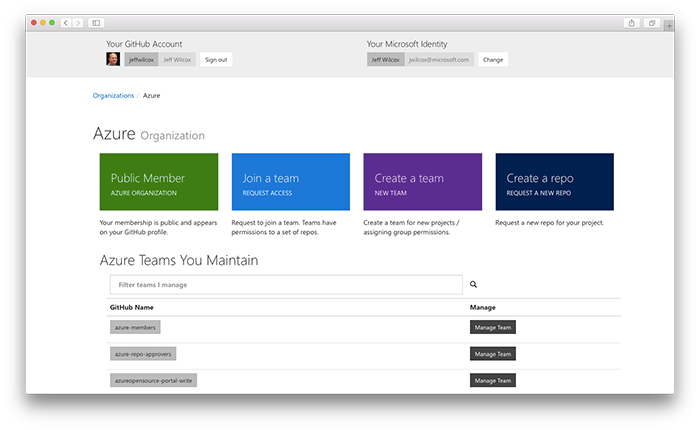

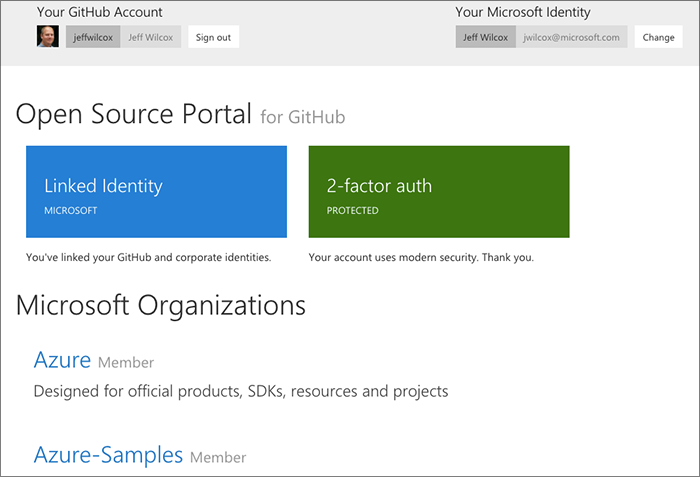

The Azure Open Source Portal for GitHub is a web app that lets employees authenticate with GitHub, authenticate with Microsoft (via Azure Active Directory), create a "virtual link" of these identities, onboarding to our organization(s), and then help to manage certain tasks depending on employee role. The portal securely performs tasks on behalf of organization administrator accounts when properly authenticated and authorized.

| Azure OSS Portal: At a glance | |

|---|---|

| Source Code on GitHub | Azure/azure-oss-portal |

| License | MIT |

| Platform/Language | Node.js (JavaScript) |

| Cloud Dependencies | GitHub API, various Azure services (or contribute your own adapters) |

The portal is designed to be run on one or more cloud servers. It relies on a cache to help with sessions and to reduce pressure on the GitHub API.

Supported scale

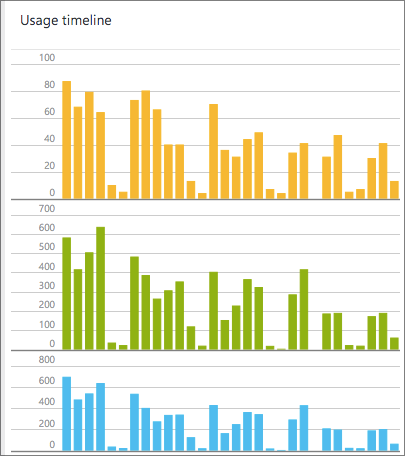

In our environment (Azure and partner teams within the company) our daily use averages around a thousand unique users. This is not an app designed for production web traffic as much as a tool for your engineers.

Although we do have users from around the world, much of our traffic comes from the Redmond area and resembles a pretty classic tech work day schedule. Here's a look at the traffic graph that Visual Studio Application Insights produces for us in the Azure Portal:

This portal as implemented can likely support organizations or engineering groups from 1-10,000 members if the organizations are already established.

To get to the next order of magnitude we may eventually have to build in a smarter cache and rate limiting to the GitHub API, but today we never approach our GitHub API rate limits since the average use over time is pretty low. We tend to have several net new joins and a few departures over the course of a week, but rarely do we have more than 100 users join the org through our portal in a day.

Any OS

As a Node.js app the portal can run in many environments. In my development environment I regularly develop on my Mac or use my Ubuntu workstation and have really enjoyed using Visual Studio Code in all its cross-platform glory.

Requirements

- Node.js LTS release (Node.js 4.2.1, 4.2.2 or newer)

- A Redis server

- Azure Active Directory (for corporate authentication)

- An Azure storage account (for table storage)

Though I will cover it later in the post, I'm very open to working with potential contributors to remove some of the opinionated technology and policy choices in the portal. Together we can build something great.

Open Source projects used

Front-end components used in the project include Bootstrap, jQuery, and several small jQuery plugins.

The following Node.js modules are also used:

- applicationinsights

- async

- azure-storage

- express

- jade

- moment

- node-uuid

- octonode

- passport

- passport-azure-ad

- passport-github

- redis

(Also, these dependencies have their own dependencies which are equally important)

I contributed to Octonode OSS

As part of the building of this portal, I've contributed to the octonode module, a Node.js service wrapper for the GitHub API, created by Pavan Kumar Sunkara. Thank you for your great library! I was able to contribute a number of updates related to the October GitHub changes that happened relating to organization permissions management as well as adding endpoints that had not yet been needed by other users of the library. The library is a clean, simple CoffeeScript library.

Service Dependencies

The portal makes use of a number of Azure services:

- Azure Active Directory

- Azure App Service

- Azure Storage - Table Service

- Azure Redis Cache

- Azure KeyVault

- Visual Studio Application Insights

App Insights is optional, as is KeyVault.

You can bring your own app server and Redis.

Swapping out table storage with your own storage preference would probably take 30-60 minutes.

And if you have a Passport (Node.js module for OAuth libraries) module that you or your organization uses, you could swap that out pretty easily for AD.

Azure Active Directory

Azure Active Directory allows for single sign-on to cloud apps and can integrate with on-premises Active Directory. Our portal makes use of the Microsoft tenant and also the team's open source Node.js modules for working with it.

With Azure AD we are also able to have corporate multi-factor authentication for extra security (separate from GitHub 2FA).

Azure App Service

Azure App Service is a powerful web hosting platform (and a lot more).

App Service handles running and deploying the web app straight from GitHub, is highly available, plus offers role-based access control for the app configuration.

The service could also be deployed using Cloud Services (our rock-solid PaaS offering) or with Traffic Manager and many multi-region App Service deployments.

In a pinch the Log Streaming feature makes real-time diagnostics and tracing a little easier, too.

Azure Table Storage

Azure Storage is our reliable cloud storage and in the OSS portal we use Azure Table as a geo-redundant NoSQL store for:

- "Virtual Links" connecting GitHub and employee identities

- Information about pending requests to join teams and create repos

- Errors optional: help drive bugs out of the product

- Audit logs, optional, depending on your compliance needs and location requirements

In past portal versions we also used table to store settings for teams, a list of team owners, and other functionality which has been superceded by improvements made by GitHub to their organization management system in October 2015.

Azure Redis Cache

The Azure Redis Cache service is Redis-as-a-service and makes it really easy to build out the cache layer without worrying about ops.

The cache is used for session storage and also for caching GitHub API responses, often with time-to-live (TTL) parameters set. This helps reduce pressure on the GitHub API.

We then use the standard Redis libraries for Node.js and express-session.

Azure Key Vault

With Azure Key Vault we're able to safeguard the important keys and secrets used by the portal.

At this time the open source version of the portal does not integrate with key vault. We'll improve this in the

future as capabilities allow. Instead, a simple configuration.js integration point allows for any async configuration

and secret provider to be used at app initialization time.

Visual Studio Application Insights

Visual Studio Application Insights has two important functions for our app: getting insights from client browsers and then also for monitoring the Node.js app's performance, including latency and error rates.

Since our portal is built on top of the GitHub API, there's a potential for high latency as every important action has to hit the GitHub API on behalf of either the portal user or a portal administrator.

AppInsights helps us keep a handle on this, general use patterns, and see how we are trending.

Portal Features

Now let's look at the user scenarios and management features that the Azure Open Source Portal for GitHub implements at this time.

Essentials

Self-service

An employee can use the portal to join one of our GitHub organizations at their own pace, without a manual invitation being sent from an administrator.

This is accomplished by tying together the GitHub API, GitHub OAuth support for users/applications, and Azure Active Directory.

Corporate policy

We can educate, inform and enforce our corporate beliefs and policies regarding open source thanks to the portal source portal.

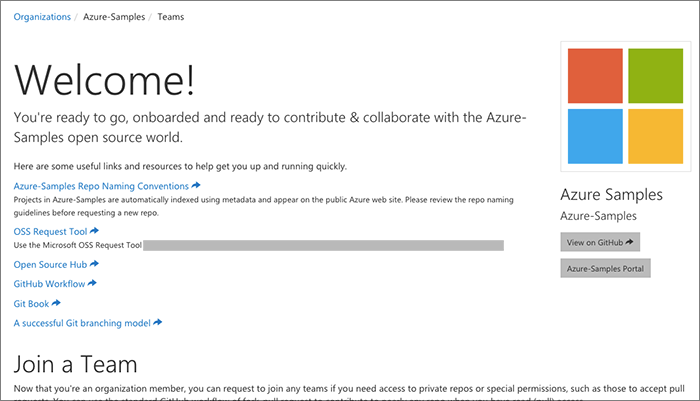

Since users onboard to our organization(s) through the portal, this is a great chance for us to share with them links, training and educational resources. Not only about policy, but also about generally useful info: Git tips and tricks for teams, how the GitHub fork/pull request workflow is best implemented, and where to find the Git Book.

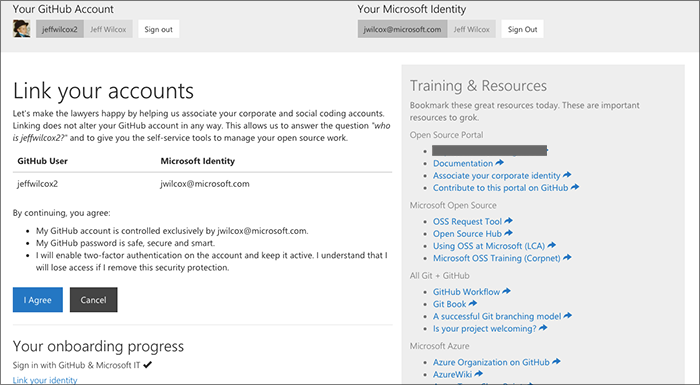

GitHub user ID mapping to corporate identity

The portal creates a "virtual link" between a corporate identity and a GitHub ID. A GitHub ID is constant: even if a user changes their GitHub username, the link will remain. We of course also then have the two-way mapping between usernames and corporate identities.

This link is possible because of OAuth:

- The GitHub identity comes first, from the GitHub OAuth flow

- The corporate identity comes next, via Azure Active Directory (or your own Passport provider and a few hacks)

- Table storage to tie these two values together for the portal and its systems to reason over

At the top of every page, employees will see both their GitHub and corporate identities.

Early on in our attempts to use a JSON file to map employees to GitHub usernames we regularly found that users would rename their GitHub names: often they started with a name or nickname, then as they contributed more, would step back to create a more "professional" profile with their name, a nice photo, and often a username rename.

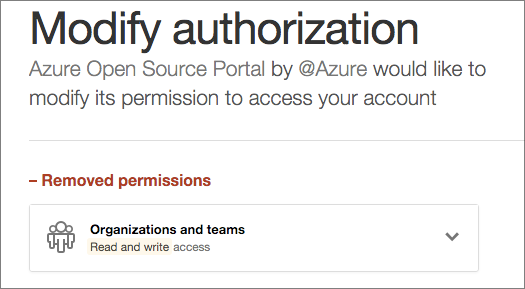

Low-impact GitHub application scope

The portal makes use of minimal GitHub OAuth scope by default. It does not require access to a user's private repos, organizations or settings.

This helps to establish trust (along with the portal being open source).

There are a few codepaths within the web app that require an increased scope, however: the write:org scope is

optionally needed to perform two actions that make a user's experience better:

- Accepting their invitation to one of our organizations via automation. The GitHub invitation process can be easy to miss in e-mail inboxes. If a user does not increase the scope, we walk them through accepting the invitation on GitHub.com and then returning to our portal, but with the increased scope we can use the API to accept the invitation and move them on automatically.

- Publicizing a user's membership in an organization. The same org write scope is required to make organization membership public. We want people to understand that Microsoft and Azure are very serious about being out in the open source world and on GitHub, so we want to encourage our users to publicize their membership if they are comfortable doing so. Although they can make this choice on GitHub.com, it is kind of hidden away and difficult to describe how to allow a user to publicize, so the API just makes this easy.

We ask at the time that these actions are required to increase the scope so that users are not "scared away" upon their first use of the portal. The next time a user signs in to the portal, the increased scope is removed.

Our application does not store user tokens long term.

GitHub API on behalf of owners

The portal uses the GitHub API V3 on behalf of an organization administrator to automate tasks such as inviting users to GitHub. It makes heavy use of the subset of the API for organizations.

Corporate OSS identity homepage

We surface the high-level basics to a user:

- We know what their identity is

- Whether they are using multi-factor authentication with GitHub

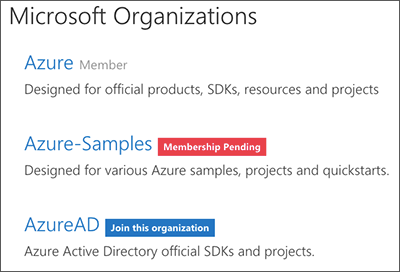

- What organization(s) they are a member of, and the ability to join additional organizations

Showing corporate identities

Thanks to table storage and the "virtual links" for corporate users, we can show the Microsoft corporate identity ("alias" is a common term we use), a link to their corporate profile page and hierarchy, alongside their GitHub identity.

If a team maintainer wishes to add an existing organization member to a team, they will see a large drop-down list with corporate identities first, GitHub usernames second, so that they can quickly use the keyboard to narrow down the employee they want to grant access to, without having to lookup the user in a big table.

Corporate and organization resource links

A simple resources.json file, checked in to the project, is meant as a place to provide links

to corporate information on open source or any other resources you would like to point users at.

Some resources appear at the bottom of nearly every page in the portal. Others, like the corporate resources, appear during the initial "link" process.

Organization-specific resources are also supported. These are highlighted to users when

they first join an organization. We use this feature to show users naming convention for

repo requests, for example, for the Azure-Samples organization.

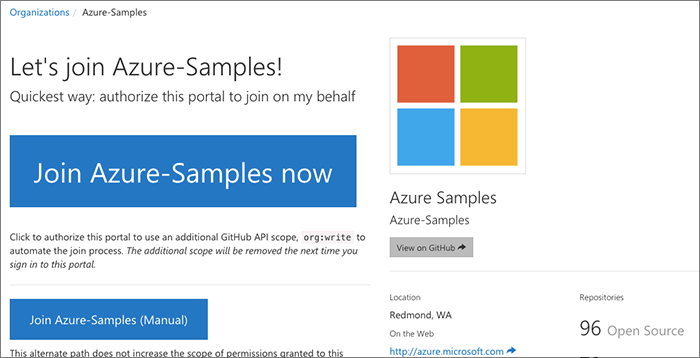

Helping users understand our investment, private repo availability

We want our users to also understand the scope of our investment in GitHub. For any organization, we will show them the number of total repos, the private repo allocation that we have paid for, and other important information. We surface this both during the organization join process as well as at the bottom of the organization sub-pages on the site.

This also helps users make smart decisions about whether they really need yet another private repo on their march to open source. (Microsoft has great open source internally and plenty of places to store Git repos... so we do not permit projects to be hosted on GitHub which are not intended to be open source and on that path already).

Mobile friendly

By using Bootstrap, we get a nice mobile experience for the portal.

This has really helped reduce the mean time to handle permission and repo requests.

Whether you're on the bus to or from work or out on the town but still connected, team maintainers and organization administrators are able to quickly authorize the action just through an e-mail and a quick touch on the portal.

Wizard-style Onboarding Experience

While it might seem odd at first glance that we're asking employees to use a separate web site to get going with GitHub (vs just using GitHub.com), one way in which the portal really shines is in its onboarding experience.

If you maintain a large GitHub organization as an administrator today, you probably know what I'm talking about: endless e-mails asking for invitations to be sent, team permissions changes, repo create requests, etc. I've been there, too.

Over the years we have found that the onboarding experience is one that is hard to teach: even if we create a rich document or wiki page walking users through the process, they often glance over pretty important parts.

Our curated onboarding experience is one of the key values of the portal.

I'm now going to walk you through the onboarding experience with a lot of screenshots... hope you have an appropriate mobile data allowance. When there are branches in the flow, I'll try and explain what those are.

Signing in to GitHub

Users first use OAuth to sign in to the GitHub application for the portal. We only authenticate with GitHub but do not need scope to perform actions on the user behalf initially.

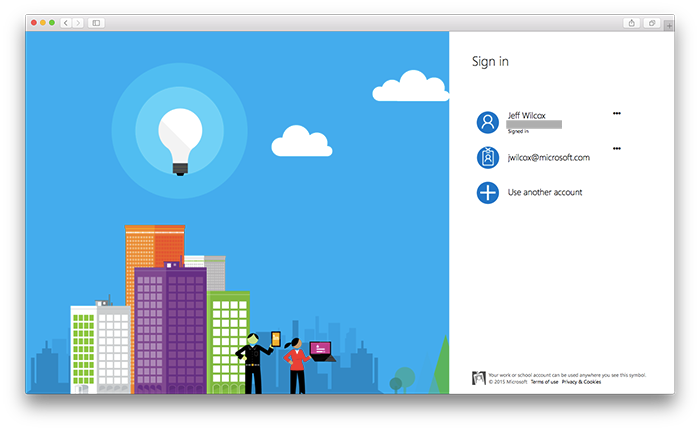

Signing in to Microsoft

Next, Azure Active Directory takes the user through authenticating with the corporate environment, including multi-factor authentication if it is configured on the tenant.

"Linking" the accounts

Once both GitHub and Active Directory have authenticated and we've decided to authorize the user to onboard with us, we ask the user to confirm that they would like to start the onboarding process.

This page exists so that we can share some helpful resources and links to training, where to go for more information, and general policy reminders.

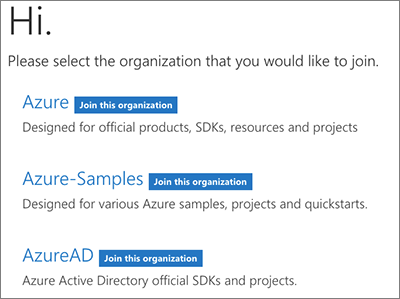

Joining your first organization

The user then selects the organization that they want to join. At this point in the process, although we know who the GitHub user is as an employee, they are not a member of any organization, nor have they been invited to an org yet.

Invitation process

After selecting a page, the user is given some overview information about the organization's presence on GitHub:

- The organization name

- The purpose and description of the organization

- Information about the # of allocated and remaining private repos for the org, if any. (We stage work ahead of events privately on GitHub.)

Now the important part here is that we would like the use to hit the large "Join now" button, but we need to warn the user ahead of time that we will need to expand the authorized GitHub scope for the app a little to do this. It makes everything a lot easier, but we completely understand if the user does not want to give additional scope.

Behind the scenes, when you hit Join Now, we:

- Send an invitation from GitHub to the user, from the organization, to join a special team used for onboarding

- If authorized with the user's

write:orgscope, we will update their membership to accept the invitation from the organization - The user then is a member of the organization, so we're able to use the GitHub API to determine whether the user has two-factor authentication turned on

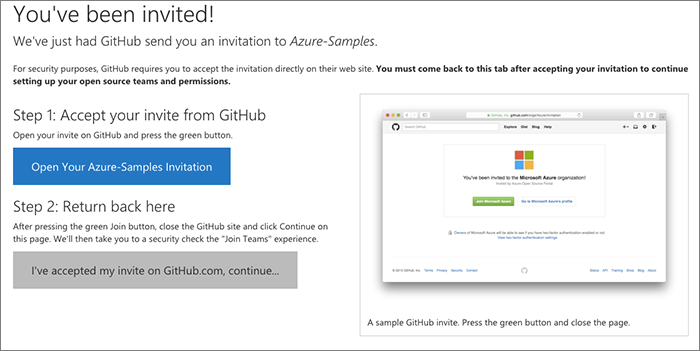

Manual join process

If you do not authorize the additional scope for us to automate the org accept, here's what the alternate looks like:

Here we:

- Explain that we are about to send your browser over to GitHub to accept the invitation manually

- Explain this again when you click the button

- Send you to the org invite page

- Hope that you will then come back to continue the onboarding process. If you do not, you will only have access to the initial team used during onboarding.

We have continued to fine-tune this over time as users have sometimes ignored the process at this point and then not had the access they were hoping to have.

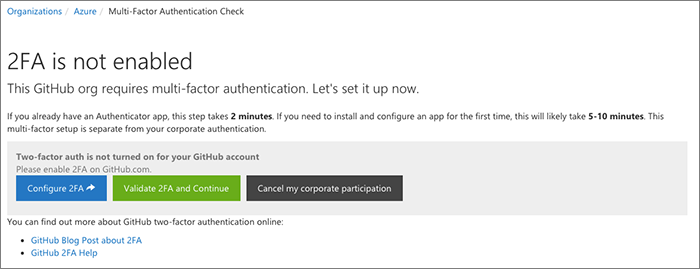

Security check

We perform a security check next where we use the GitHub API to determine whether the user has enabled two-factor auth with GitHub.

If they have, they never see the security check page, they are redirected on their way.

If 2FA is not turned on, the onboarding process will halt here until they enable it.

In the future, if the user removes 2FA from their account, the next time they go to the portal we will similarly block them on the same "please enable 2FA" page.

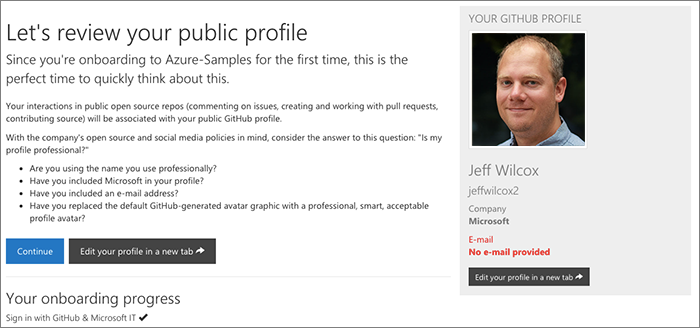

Profile review

After some feedback this year on the portal, we've added in a "profile review" page where we offer the user a chance to see what their profile will look like on GitHub.

The company has social network guidance and as part of this we want to make sure that people understand when they may not be aligned with that preference. We will highlight in red any fields that feel out of compliance, for example, not including an e-mail address.

This is an informational step only.

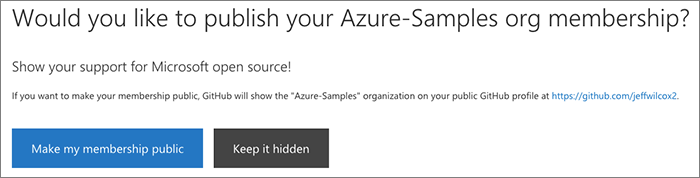

Publicizing your organization membership

We then ask the user if they would like to make their membership in the organization public. This choice is up to them, but we have found that offering this as a simple button is an easy way to help people feel good about their participation.

If they authorized us already to use the write:org scope in this session and they

have decided to make it public, we'll do this on their behalf.

Final steps and user education

Finally the user's successful onboarding is acknowledged. They receive a nice 'Welcome' banner and are on a dual-purpose page: it shows links to resources specific to the organization and also an opportunity to request to join teams within the organization.

Join teams

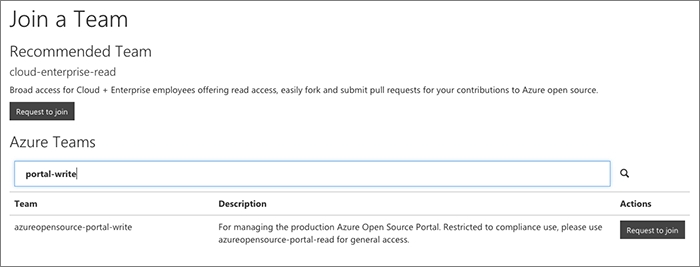

The teams page shows all of the teams in the organization along with any available description. The list can get quite long for some orgs and so can be filtered.

Join another org

Once you've joined your first organization with the portal it's much quicker to join any other orgs that you need.

For extra orgs we skip the profile review step.

Completing a join

If users do not authorize us to accept their invitation automatically, we sometimes have found that the standard GitHub e-mails end up getting lost in the ether, and so invitations remain unaccepted, and users confused.

We show the status of org membership, including any pending memberships, on the homepage for the portal. Users can pick up with the onboarding process wherever they left off last time.

Offboarding: Leave corporate OSS

To help prevent data loss, we want to make it very clear to a user that they may lose private forks and pending work if they leave the organization(s) too soon. This is shown on the "Leave (ORG)" or "Remove corporate access" buttons in the site.

Of course organization members are always able to leave organizations directly on GitHub.com. We have a service which runs looking for users who have left the org to remove their virtual links. Often when an employee is about to leave the company they may chose to leave their organizations proactively, for example.

Enforcing two-factor authentication

100% of our users who have come into the organization by way of the portal have multi-factor authentication turned on.

If users turn off this enhanced security after joining the organization, upon trying to use the portal, they will encounter the same 2FA block until they enable it and we can verify that using the GitHub API.

We also try and educate our users about the GitHub feature of Personal Access Tokens, which can be revoked, as a replacement for password use in certain Git tools and workflows.

This was also coverered in the onboarding section.

Supporting multiple organizations

The portal supports any number of GitHub organizations.

Each organization has independent configuration and security token support:

- The organization name as you would like it to be shown in the portal (i.e. we show

AzureADinstead ofAzuread) - An optional type of organization (do you want to support private repo creation?)

- A description about the org's purpose, high-level goals and ideal type of project

- A token for managing on behalf of an owner account

- A private (or public if you wanted) repo for posting issues for approval workflows to join teams and create repos

- Optional configuration for other light-up scenarios that we manage using web hooks

- Teams to highlight to users for suggesting team joins: i.e. "This is our huge READ access team that you should join for accessing a TON of stuff that you might need to do your job"

When I first hacked together the portal, I built it to only support a single organization. Once it became evident that we would need to support many organizations, the first refactoring added on the concept of "leaf node" organizations: you would join the primary organization during onboarding, and then after that be able to join any other organization. In today's implementation we instead have moved to support any organization without a concept of a primary org.

Although the portal centers most operations around drilling down into the org level, we've also experimented with building a cross-organization view ("I need to join a team, but don't know where it is" or "can I see all the teams I maintain across all orgs?"), but they rely pretty heavily on Redis right now and are not the most efficient calls.

Building blocks for value-add webhooks

The app includes scaffolding to enable rich web hook interfaces within your organizations. We are migrating a number of pre-repo webhooks to instead be organization-wide for tasks like gathering statistics for operations, refreshing special team lists and caches, and our Azure CLA Bot.

Team join and repo requests

We have a few workflows built into the portal. The requests are stored inside of table storage and the issues and notifications are done by using GitHub issues within a repo for the organization involved in the decision. Although the repo could be public, we recommend keeping it private. When a request is opened, all potential approvers are shown to the user making the request, and also we "@mention" all of the users in case another one other than the randomly assigned owner can get to the request sooner.

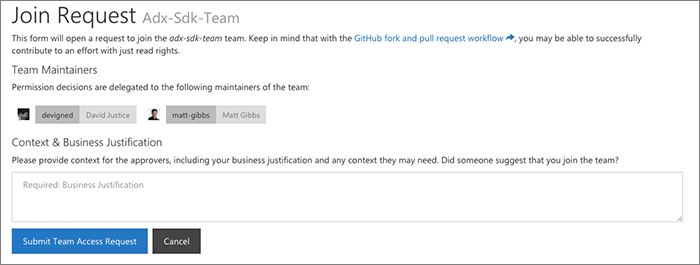

Allowing users to request access to teams

From the portal users can request access to join a team. The request generates a GitHub issue to have a team maintainer review the request.

This is a very important part of the portal: delegating requests to the individual teams that are best positioned to make a decision. This is an important part of scaling out the experience of managing a large org. We've actually had this workflow for a long time now, pre-dating GitHub's team maintainer concept (we called ours 'team owner'). As a result we have kept this workflow, but users can also request to join a team directly on GitHub.com now, and that request goes to team maintainers. The verdict isn't in yet on whether we prefer one or the other, but I personally like that our workflow includes the ability for the requester to submit context.

With a very large organization (hundreds of teams), we've found that without a piece of context or business justification, often maintaines would get a request from a random individual in the organization. Often times that random person simply wanted to get involved and help contribute to a project but did not understand that the GitHub fork function would let them contribute a pull request with their read (for a public repo) access. With the context it's easy for the approvers to understand what the person is hoping to do, and then we're able to keep that context for future maintainers, too, so that the institutional knowledge of why a request was approved lives on.

Repo create requests

Just like permission requests, we've decided to insert a small roadblock into the repo creation process.

The requests go to a team of people for the org who are responsible for approving repo requests per their standards. Each org often has its own naming guidelines and preferences.

This is also a great time for us to confirm with teams that they are working toward open sourcing a project (for private repos) or that they have legal approval to publicize their project (for public repos).

Since the approval is a GitHub issue and then a very simple action on the portal, there's no manual work involved in creating repos on GitHub, mispellings or typos, etc.

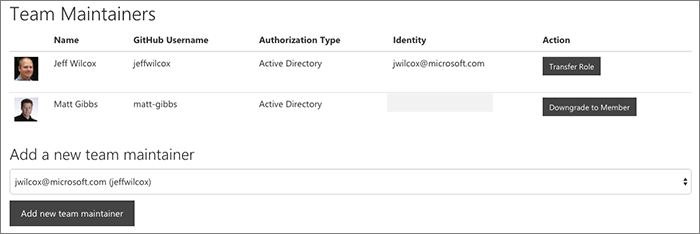

Portal Management Features

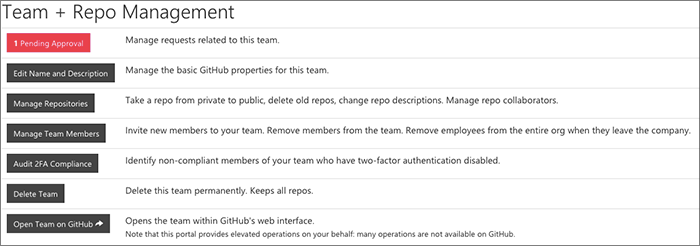

Team and Repo Management

Team maintainers are able to go to a URL which is //site/orgname/teams/team-name/ and provides a full suite of management operations.

The key concept here is that we let team maintainers make administrative decisions regarding their repos.

Per-organization approvers

Each organization has its own configuration. For an org you're able to tag a GitHub team as a "repo approver" team - those are the approvers who will be able to make decisions about new repos for that specific org.

Since the team is just a GitHub team, that means that the maintainers will be able to transfer their responsibility, add additional approvers, and manage situations such as vacation breaks, without having to involve the central GitHub administrators.

Past complexities...

In the past we had a lot of gold-plated, advanced features: allowing pre-approving employees to join teams automatically, allowing third parties to join the organization, etc. Over time, and with GitHub changes to their permissions models, we have evolved and simplified this.

How we offer extended permissions to team maintainers

We extend additional capabilities to our team maintainers.

If you are a team maintainer, within our separate portal, we will let you perform administrative actions on all of your repos. Most of the operations are for tasks such as taking a repo public, renaming a repo, updating the description, etc.

| Member Role | GitHub.com Capabilities | Azure OSS Portal Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Org Admin |

|

|

| Org Sudoer | Not a GitHub concept |

|

| Team Maintainer |

|

|

| Team Member |

|

No special capabilities other than viewing team membership. |

Note that we originally considered a slightly different scheme: if you were a team maintainer, and your team had write or admin capabilities, then we would give you this permission. It turns out we require our team maintainers to have some skin in the game, so it didn't really make sense to get more granular.

With the October updates to the GitHub permissions model, it's also true that we now allow a corporate collaborator to be assigned to a repo with admin rights, so there are other ways to easily get access to these properties now that were more difficult in the past without creating a ton of teams.

Helping team owners check 2FA compliance

GitHub's API allows us to query for 2FA compliance across our organization, but does not typically give this information to team maintainers.

Although our 2FA compliance is very high already, we of course would always like the compliance to be even higher.

To help with this, we give team maintainers the ability to get the list of their members who do not have it turned on.

Outside and corporate collaborators

With the October update from GitHub, they're reintroduced the concept of a Collaborator for organization repos.

This has helped us evolve our portal and permission model: we used to have a very complicated system for authorizing external third parties to join our organization through special teams designed for collaboration.

Now we can make smart choices about specific repos to invite people to help or review our work.

The portal surfaces this through the "Manage Repos" > "Manage Collaborators" feature.

We have 2 types of collaborators:

- Outside Collaborator: this is a GitHub username who is not registered with a link in the system.

- Corporate Collaborator: this is our concept, it's just a collaborator for a repo whose identity at Microsoft is known. This makes it easy to add employee collaborators, since you can use their corporate alias/e-mail for the operation.

Integrating with GitHub-native team requests

As a recent change in October 2015, with the new organization permissions model, users can request access to a team from a Team Maintainer directly on GitHub.com. We do not get involved in that separate process today - the maintainers will get a GitHub e-mail and hopefully respond to it, but we do not surface those requests inside our portal.

We prefer right now that team joins use our tooling, since we are able to ask for a business justification to keep along. We figure, over time, that with new maintainers and owners over the years, that context could be important.

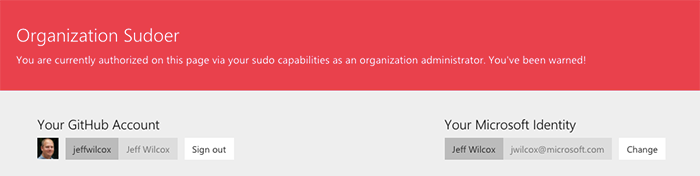

Organization sudoers

On the Azure team we do not allow any of our employees (including me!) to have administrative rights over our GitHub orgs.

Instead, we have a team in each GitHub repo that is effectively a "sudoers" list.

Members of the team are able to perform a subset of organization management operations inside the portal, as well as have sudo rights over all the teams in the organization.

This is useful in the case that a permission request is sitting with a team whose maintainers are out on holiday, for example, and can help with escalations.

Inside the portal we have a big warning, though, for the users when they are viewing and authorizing as a sudo user.

Administrivia

Identifying ex-employees

We have on-premise tools at Microsoft that let use query LDAP for our employees. We've connected this tooling to an endpoint on the portal, allowing us to get the full list of expected members of the organizations with the current LDAP records.

This work isn't open sourced right now because it's very fragile and company-specific to our internal infrastructure, but it would be easy to generalize this probably.

Depending on the permissions for your app in the Active Directory, you might be able to actually do graph queries from the site directly, but it's a long approval process for us to go through, so instead I've chosen to write the app as an on-premise thing.

Service Banner

The application looks for an environment variable called SITE_SERVICE_BANNER by default.

When set, an alert banner will be placed at the top of every single page in the portal to signed in users. This is useful for sharing service availability metrics or informing the users of breaking changes / performance issues / etc. This was especially useful as the app was updated to support the new changes that GitHub made to their APIs in October.

This feature feels necessary because of the dependency on a third party API for nearly all functions.

Integrated error tracking

Errors can be logged in the default Node.js logger instance. This has helped to minimize the number of bugs over time.

GitHub org management decisions we have made

Kicking out our administrators

Time for a quick side story...

Those of us who were interested in working to improve the management experience for GitHub learned of a key opportunity for us to shift our GitHub management tooling and processes in March 2014: we announced that we were rebranding our cloud platform from the name Windows Azure to Microsoft Azure, effective in April.

With a short runway in place, we realized that instead of renaming our organization, we could

actually create a new Azure organization, build some tooling to help replicate our team

permissions, and then transfer repos when everyone was ready. Oh, and none of the admins

of the Windows Azure organization were going to be admins on the new org.

Moving away from our wild-west manual management world was an important step in our OSS maturation, but we did experience growing pains. Our system that helped map employee identities to GitHub usernames was essentially a single JSON file that described this mapping, teams and members, and repos. Once a manual invitation was sent to someone to join the organization, they could then fork and submit pull requests from the private GitHub repo that contained this JSON file. Tooling automatically would run to update the organization by goal-seeking to the desired state of the JSON file. Team management was possible, but onboarding and getting started was not easy.

Role-based Administrator/Owner Accounts

For a number of reasons, our organizations are not owned by individual GitHub usernames.

By not granting anyone direct admin access with their standard GitHub identities on GitHub, everyone has to play by the same rules, feeling the pain of the same tooling and systems that we have in place, and there's less risk for an accident: since owner accounts can push to any repo and alter any GitHub "Danger Zone" setting, it's a lot of power for regular accounts to have.

Instead we have a number of accounts that are secured and used only for administrative operations. These are assigned to specific people who help run the organizations, but only for key org uses - configuring application settings or generating tokens for our secure infrastructure to use. These users do not regularly use the accounts. The accounts are set up so that they can be transferred to others as we rotate the administrator stakeholder role over the years.

Billing: Yearly purchase order invoice payment

We recently switched from monthly Amex invoices to covering a number of our organizations under a single purchase order/invoice system. This makes our process a lot more lightweight.

October 2015 GitHub changes - org permissions model

In October 2015, GitHub launched a set of great improvements to organization management. Thanks, GitHub! They did a very good job of communicating early and often about the upcoming changes.

It's up to organization administrators to select the set of new organization permissions features they want for their org members. Here's how we have landed on those decisions for the most part:

Team privacy: We have made our teams visible for the most part. Our portal shows all teams traditionally, so users are used to having the full set of team options available to them.

Repository creation: We do not allow our members to create repositories at this time. It's a debated topic and one we will probably review over time. Our approval process for new repos is an important but lightweight part of the open source workflow for teams and is a good point to ask important questions, collect a business justification, confirm whether we're happy with repo name choices, etc. If GitHub allowed us to lock down the ability to take a repo from private to public, we'd be pretty happy, because it's just the act of going public which is a very important thing for us to get right.

Default repository permission: At this time our decision for this setting is "None", though I think we'd really like to move to the "Read" model. Using our OSS portal many users effectively get "read" access to a large number of repos after the onboarding process, so the impact is small, but we really want to be open and transparent inside the company when it comes to private repos, since the only work on our GitHub is work that is destined to be open source in time.

Third-party application access policy: We are trying this feature out and have restricted access. We are allowing individual applications (there's a bunch of important and popular services, like Jenkis and Travis CI) on a case-by-case basis.

Contributor License Agreement (CLA)

Our internal implementation of the portal exposes an endpoint that the Azure CLA bot can use to query information about our users.

You can read more about the Azure CLA Bot on the Azure Blog.

In time we would like our CLA bot to automatically be registered with any new repo request.

Org-wide Webhooks

We have a number of web hooks that happen at the organization level to help with compliance, our portals, gathering statistics, and other tasks. We are actively trying to be more consistent by moving hooks from repos to the organization when they are general-purpose and provide value for others.

People leave companies, too

Microsoft is a great place to work and I'm proud to have worked here the past 10 years. But I realize that that's a long time, especially in Silicon Valley Years (SVY).

Employees try new things and new careers all the time, and at our scale, we need to have automation to remove access when people move on.

To do this, on-premises we have an app that pulls data from the open source portal through a "friend endpoint" containing all current members and any links we are aware of. We can then use that to compare with our corporate systems. Members that are identified as no longer being with the company are removed from all organizations managed by the portal.

It might be possible to implement this using AAD as well and then use something like an App Service WebJob to regularly run through the directory, but for now it remains on-premise and not a part of this project.

Business justification records for our future replacements

In the same way that people leave, in a corporate scale environment, we're likely not going to be a permanent administrator of GitHub, and our team maintainers are not going to permanent, either.

By storing a business justification along with requests, we're able to have some context available inside the portal for future maintainers as we pass the baton on to them.

Portal Implementer's Guide

This is not an exhaustive guide but rather a starting place if you're looking to hack around. Please reach out if you want to get serious about integrating this with your own work. After a CLA we can start collaborating on refactoring and more.

Dependencies / Requirements

You will need:

- An Azure subscription (for AD access, table storage)

- An Azure Active Directory (easy enough to setup your own tiny directory if you want)

- A Redis cache server (or Azure Redis Cache), or a few minutes to hack the app to skip using Redis, if you're just experimenting

- A GitHub organization that you own or can get access to create an app and generate a token credential

Help offer more choice! Contribute!

Since the project is open source, I would love to see someone who is interested in helping to abstract out many of the opinionated decisions made in the original implementation (policies around organization management) as well as the technology stack.

The Node.js set of "Passport" OAuth modules are used for authentication, so any authentication provider could be swapped in with minimal effort and a little refactoring.

Though I'm using Azure Table Storage for storing the virtual linking of users, it

would be easy enough to use MongoDB, Mysql or a SQL Server - whatever you prefer. Just

hack around with data.js.

GitHub Requirements

- You need a GitHub organization (or many!)

- You will need to create a GitHub OAuth application identity for the portal, or have an administrator do this for you and provide you with the client ID and secret values tuned to your environment

- You must have access to an organization administrator account to initially generate a token with the appropriate scopes to do work on behalf of authorized users

Azure Active Directory

- You will need to have an Azure Active Directory for your company

:-)or team. Many Azure users will already have this. - You will need to create an Azure AD application to help authentication with your corporate directory

Creating a new Application entry in AAD

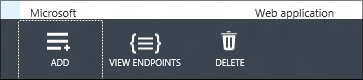

To create a new application, open up the Azure Management Portal for your Azure subscription.

Select the Active Directory section on the left and then the directory that you want to create an app for that will host the portal identity. (In most cases this is your corporate directory, but it could also be a separate staging directory or just a simple directory within your development account.)

Go to the "Applications" tab at the top of the directory and then use "Add" in the footer toolbar to create a new app entry.

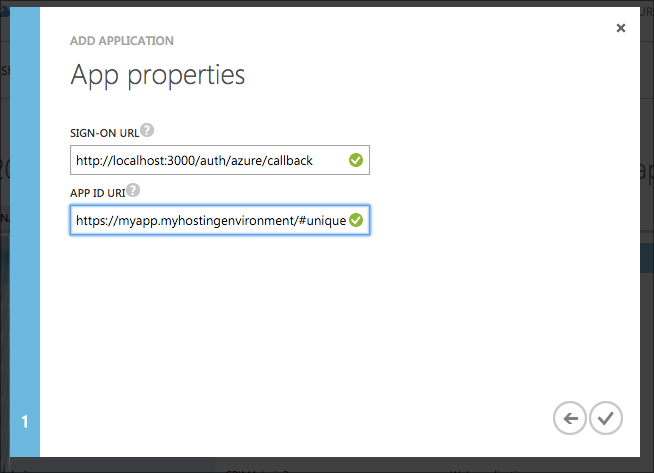

The app will be of the Web Application and/or Web API type.

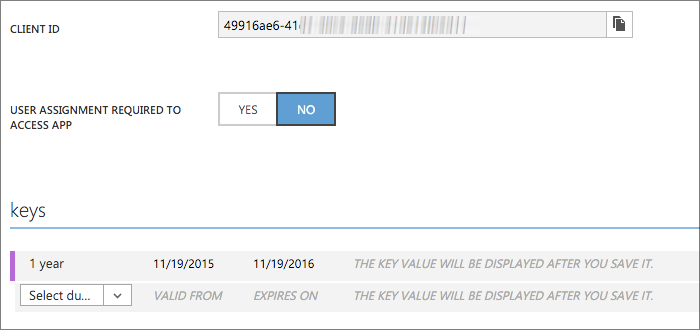

And finally from the Configure tab we'll need the Client ID and also to generate a 1-key client secret key for the app. The key is shown for the secret once you save. Make sure to store it very securely.

This operation needs to be done in the older Azure management portal, not the new one. Hopefully we can fix this at some point in Azure.

The Tenant ID will be in the URL, by the way - this is the ID for the entire directory and is a GUID.

Hosting with App Service

You can bring your own Node.js hosting platform. With Azure, you could use Cloud Services or App Service. I'm using App Service since it's super easy to set up continuous deployment and integration, plus good features like flighting.

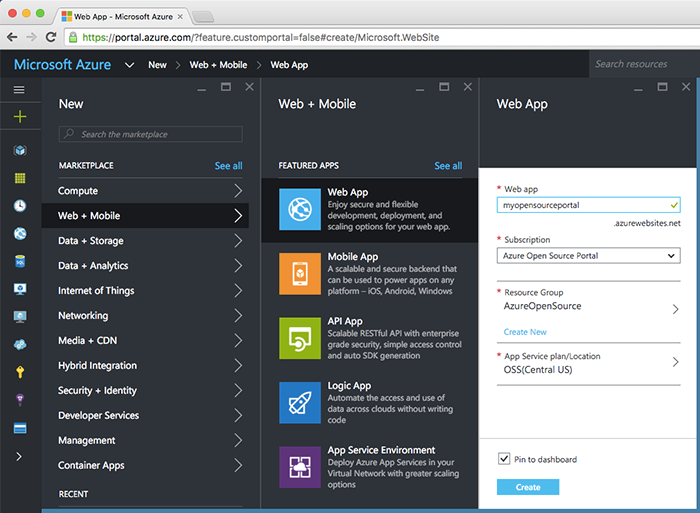

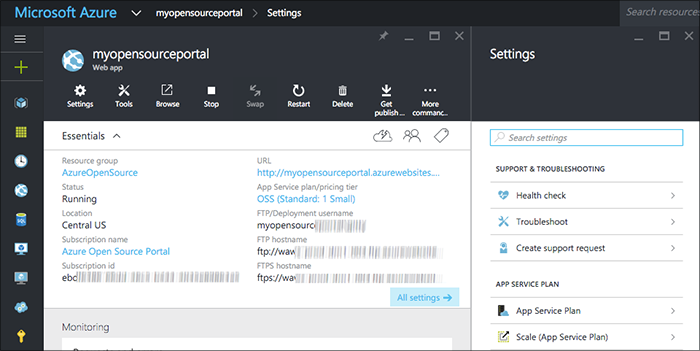

From the Azure Portal, use the New function to deploy a new app service. If this is your first time, you will also want to configure a pricing tier (or free, shared, etc.)

For this post I'm calling my app service "myopensourceportal", so it will be published to https://myopensourceportal.azurewebsites.net, using

the App Service's SSL wildcard certificate at the load balancer.

We have a lot of regions these days. I'm publishing this to our Central US region in Iowa.

We're able to support our 2,000+ users on a small instance, and for additional resilience and capacity we can easily add more instances or cross-deploy to other regions, tying them together with Traffic Manager.

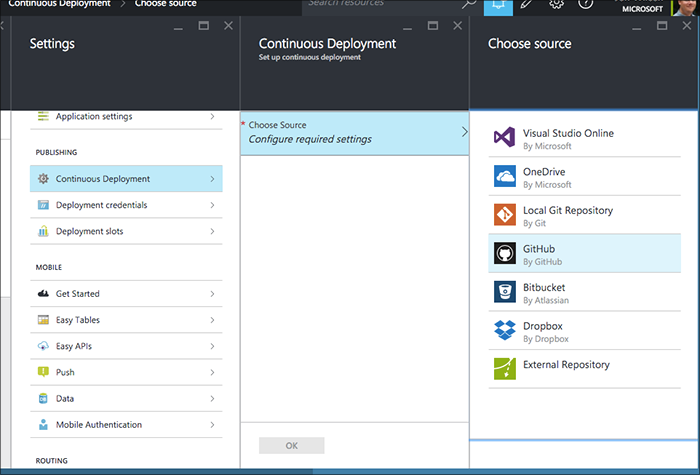

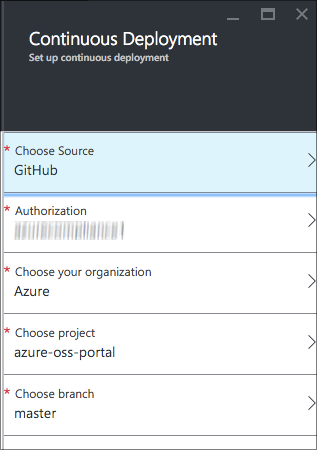

Configuring Continuous Deployment

Within the properties for the service let's drill in to the Continuous Deployment section to configure GitHub hosting.

Note: you'll need to fork the GitHub project for the portal if you want to deploy from GitHub. Alternatively you could just push from your local clone into a Git repo stored within Azure (the local repo option).

As part of the CI setup, if this is your first configuration with the Azure Portal and GitHub deployment, you'll do an OAuth dance with GitHub.

Finally, let's set this up to deploy from the master branch.

If you'd like to add additional deployments for staging or specific features you're working on (or even to do flighting, where a certain percent of your users will get sent to a different version or branch of your app), you can use the Deployment Slots feature. That's how I work to test new versions of the portal.

Configuration

The portal application builds an object with configuration properties, tokens and other shared secrets, during initialization.

The code in the open source implementation can be found in configuration.js and sets the

object's values from environment variable key names.

Credentials should never be in your source. Never!

For the most basic case, you can use environment variables to configure the application for local development.

Depending on your deployment environment, there may be a local configuration service, key management service, etc., that you can use to secure and roll credentials. For example in Azure we have KeyVault.

However, if your app and RBAC for the portal is secure, you can also get started by using the built-in Application Settings feature of Azure App Service to configure environment variables for the app.

To support real-time credential rolling, you'll need to do a little more work and use a messaging or notification platform like Service Bus.

For the easy App Service configuration case, let's configure the app! It would also be helpful at this time for you to look at configuration.js in the app source since it has the environment variable names.

Express middleware

Caching

GitHub API limits

Contributing and adapting to your own infrastructure

It would be fun to work together with some engineers out there to do some work to work with other infrastructure, abstracting away some of the opinionated policies and code in the initial open source release.

What might be a good set of work to do?

- Refactoring the code. It's clean in some places now but also a little old and crufty in other spots.

- Introducing a good Inversion of Control pattern and model to allow for company-specific endpoints, extensions and code, as well as other technologies (want to use MongoDB instead of Azure Table, for example?)

- Moving to use Promises or newer JavaScript features from newer Node/V8 releases

- Generalizing the Passport module use and design so that other directory services could be used such as Google Apps or AuthZ

Punted or past features

There's a lot of features that either have been implemented internally, or implemented in the past, or that would be important to anyone looking to take a bet on this portal.

Right now this is a list, in time I hope to either update this post or offer more information in a new post:

- Team owners

- Hierarchy-based automatic team joins

- Sponsored external users

- Expiration of accounts for interns, etc.

- Adding teams to repos workflow

- Automating 2-fa reminders after the fact

- Paging

- More intelligent caching

- Helping people find the teams they need to be a part of

- Educating users better on GitHub workflow vs write permissions

What's Next?

My personal GitHub wish list

In the chance that this post is honored with a reader or two from GitHub, I figure this is as good time as any to share my personal organization-related GitHub wish list:

- The ability to plug in third-party authorization endpoints or systems like Azure Active Directory (Enterprise does have more auth choices, but I am talking about the public GitHub experience where our outbound open soruce work often goes)

- The ability to lock down repo creation to just public repo functionality, allowing anyone to create a private repo, but not go public - we want 'public' to be a special thing!

- Allow Organization owners to require 2-factor authentication. Members who do not have 2FA should be enforced then by GitHub.

- Fine-grained org permissions: allow people to manage their own teams for repos (similar to Collaborators) out of the set of approved organization members, similar to how we have expanded the Team Maintainer ability within our portal, for example.

What's Azure doing on GitHub, anyway?

If you're interested, here's a super small subset of the projects we are working on...

- docker client contributions for Windows

- moving Markdown article content from GitHub to appearing on azure.microsoft.com (many articles have a Fork button at the bottom - go contribute and help improve our docs!)

- SDKs for managing Azure services and resources across .NET, Node.js, Java, Python, Ruby

- Command Line Tooling for Windows, Mac and Linux across both PowerShell and the cross-platform CLI powered by Node

- Mobile Services SDK for building mobile apps for building great Windows Phone, web, iOS, and Android apps powered by Azure

- Media Services (cloud streaming, encoding, live events) SDKs

- continuous integration services for teams and cloud virtual machines

- Contribution License Agreement (CLA) processing

- OAuth integration for products like Azure Websites

- Samples, documentation and resources for projects and solutions

- waagent, for managing Linux provisioning and VM interaction with the Azure fabric controller

- Azure Machine Learning modules, applications and utilities for Azure ML studio

- iisnode, for hosting Node.js apps in IIS on Windows

Why Node.js?

It might be a surprise to you that we're using Node.js, but I think it's pretty clear that Azure is all about any application platform, any OS, and I believe that for this portal to be super useful to other companies, Node.js is a pretty good starting point. It's an opinionated choice of course, but also embraces a lot of the open source innovation that is out there.

Thanks

Thank you very much to everyone who has helped with our Azure GitHub experience: the others who have helped serve as admins, the teams who have taken a bet on their technologies and workflows (such as the Azure.com team, which lets anyone contribute to tutorials and other documentation using GitHub), and those who put up with our GitHub experiences before we started moving to the self-service portal in early 2015.

Special thanks to Ivan Žužak at GitHub for putting up with a few random GitHub API questions I've had along the way.

To the maintainers and advocates for the various open source modules we are using (see also: our package.json file), thanks for taking the time and having the passion to ship something great.

And although we've moved on from some of our earlier management attempts, thanks to the Guardian developers for sharing their learnings and experiences building gu:who and blogged about it, it was really good for us to know that we were not the only people dealing with organization management growing pains and scale.

Hope this helps. Jeff Wilcox. Seattle, WA, Nov. 2015.